CT: Can you tell us about your relationship to Vancouver’s Chinatown?

M/K: My relationship with Chinatown began when I was young. I grew up in Langley, but when I was a kid, my dad would take us to Chinatown to get dim sum. We’d go to Maxim’s and go to the traditional Chinese medicine shops. Now I live and work here. I learned over the last couple of years that my grandfather owned a curio gift shop in Chinatown across from the Sun Yat-Sen Garden in the late 70s, early 80s. My dad used to joke that he would swindle white folks, sell Chinese pottery to them at a higher price, tell them they were antiques.

CT: The hustle never stops. Do you have a favourite memory of being in Chinatown?

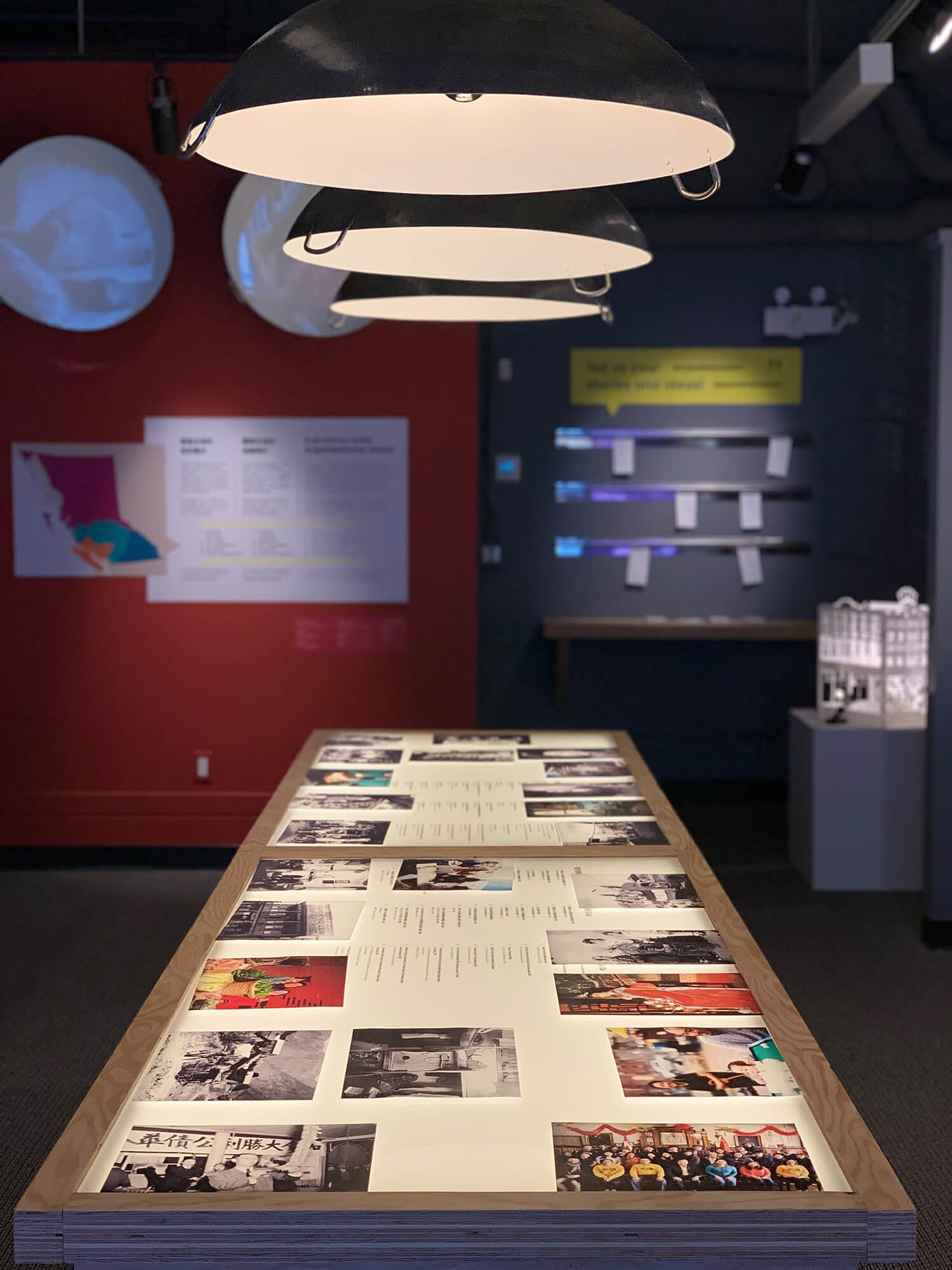

S/V: One of my favorite memories in Chinatown was last year when Paul Wong gave us an entire hall to create anexhibit to showcase the different ways the members of House of Rice represent our cultures. Dol had a table in the middle practicing Thai calligraphy where people could join and learn; Jas Minh was at the entrance serving jasmine tea for everyone; Pangolin was painting MaryKol so everyone could see the process of getting into drag; and Kara was fan dancing. Every hour, we would go to the pagoda and put on a freestyle performance. I think it was a really beautiful way of adding queer life into Sun Yat-Sen Garden. Maiden couldn’t make it because she had another event, but we put a dress on a little mannequin to represent her.

M/K: To represent my ghost. My favourite memory is doing Pride in Chinatown. I was invited along with Rose Butch to do a contemporary play on gender that was contrasted against Cantonese opera. We went to one of the performers’ homes and got to see their process, a lot of their life story, their costuming techniques, and all of their literature around the subject. Paul included a collection of my self portraits in Pride in Chinatown, which we printed on vinyl posters and plastered throughout Chinatown. My boyfriend was with me, and as we went around, I told him memories from my childhood that are linked to the different establishments and places I had been. I had this moment where I thought, “Oh, I’m taking the active role now with my partner in Chinatown that my dad had done for me.” It was spooky to come into yourself like that.

CT: I love that, it’s amazing. How do you feel that your interaction with the community or the spaces in Chinatown has changed from your first interactions to now?

M/K: It’s silly now, but when I went to Chinatown with my dad as a kid, I would think we were going to China. Looking back, that was just the most obvious way of understanding the cultural exchange as a kid, because Chinatown felt like a very removed space. Now I’m part of this space, and I see the same people on the street everyday. Chinatown sits on the edge of the Downtown Eastside, and has very complex relationships and histories. By living here, I become part of these relationships as well as patterns of gentrification. I was manager at a queer venue just outside Chinatown, and was laid off work because of COVID-19. Because of this, I’m now in a position where I rarely leave the community and the neighbourhood. As an artist who’s starting out, and as a kid who grew up in a mixed household, I often felt like an outsider even in my own culture. Because I’m so immersed in Chinatown now, I’m beginning to feel more like a part of the community.

S/V: I’ve travelled a lot, and I always find comfort in Chinatowns everywhere I go, especially because of the food. Vancouver’s Chinatown felt intimidating at first because there weren’t a lot of shops open. I don’t know if it’s because I feel more comfortable in the space now, or if there’s a growth in the number of shops, but now the intimidation has completely worn off, and I come to Chinatown quite often. Since COVID-19, I haven’t been able to come out here as much, especially because I’m a full-time frontline worker. A lot of my free time was spent self-isolating and on self-care because I’m in contact with a lot of customers. I didn’t want to risk bringing that to Kendell, so I had to separate myself from Chinatown for a while.

CT: It’s interesting you mention feeling intimidated at first. It’s something we’ve heard from some other folks as well, along with varying thoughts on policing in proximity to the Downtown Eastside. Do you have any thoughts on the implications of safety and community policing for your respective bubbles?

S/V: I had to unpack a lot of those thoughts and presumptions about what the Downtown Eastside was before I was able to be more comfortable in this space. But I don’t know if I’m around enough to witness the policing around.

M/K: Police presence has shifted pretty dramatically over the past few months, and I think it might be related to the skyrocketing number of overdose cases. There’s an astronomical number of people who are affected by the opioid crisis, and there is a lack of support from our government. I think the increase in police presence in the area is compounded because on top of the stigma around drug use in the Downtown Eastside, some folks are acting differently because they’re using new drugs that they don’t normally use. As a result, more people are calling the police, which leads to increased police presence in an already overpoliced area. You end up with a huge police presence that’s very intimidating to everyone trying to solve a problem that can’t be solved by more police.

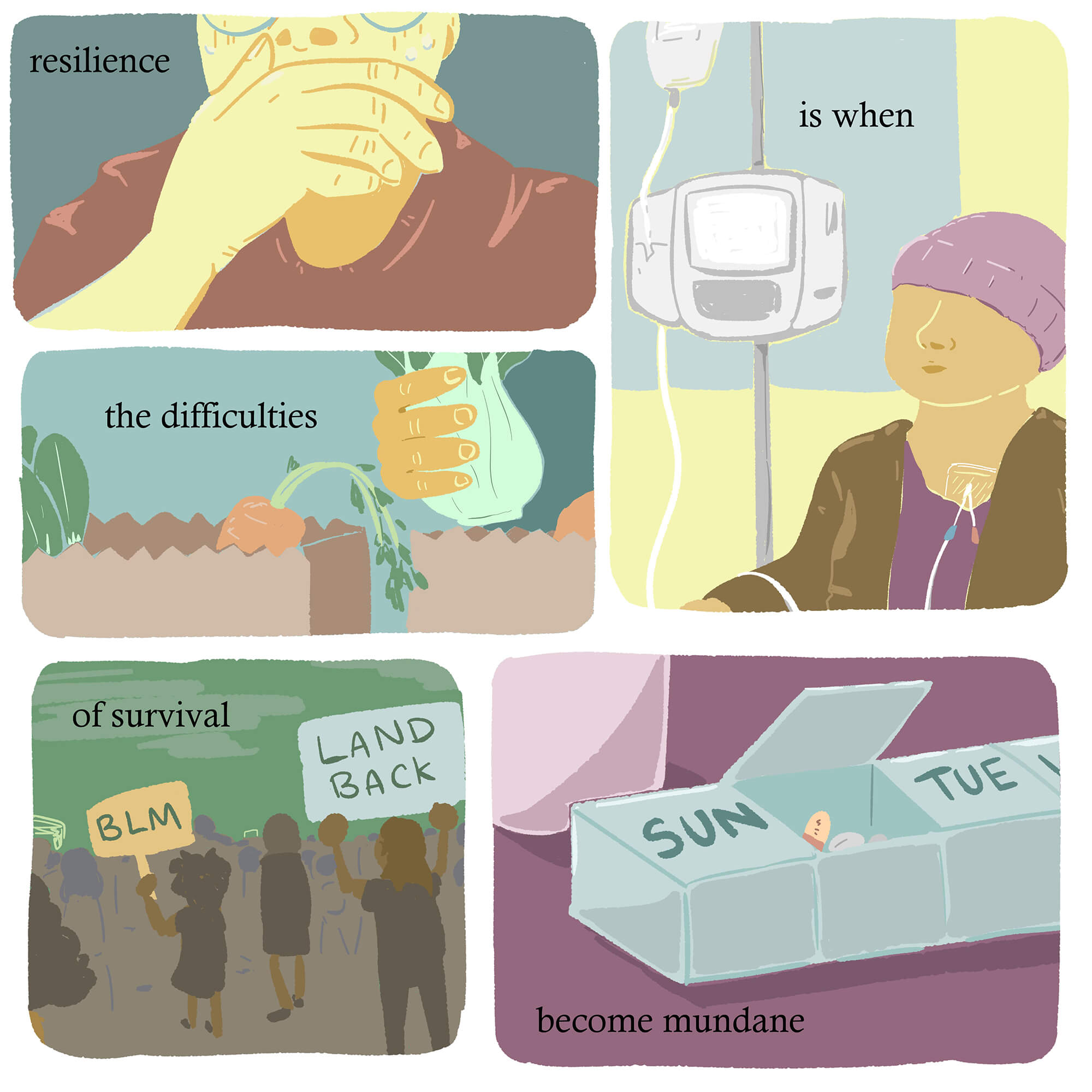

CT: What does resilience mean to you?

S/V: I feel like I’ve always had a resilient attitude. I always approach problems with the goal to make it work, regardless of the situation. The end goal is just to be happy. This year’s been crazy but I think there have been some positive outcomes. I feel like the Black Lives Matter movement wouldn’t have been as strong if everyone was still busy working. Because of the pandemic, people have free time to go to these rallies and push for change. In a sense, this virus is indirectly helping the world heal because a lot of people are being held accountable for their actions.

M/K: Resilience to me is knowing what your boundaries and limits are, but not seeing those as an impasse. My dad would always say if you’re not happy doing something there’s no point in continually pushing yourself up against it. I think a big part of resilience is knowing what the end goal is, and the things you don’t want to do. This means knowing yourself enough to change your narrative from “I’m incapable of doing that” to “I don’t want to do that”, or “it doesn’t feel good to me.”

CT: As people of colour who are not Black or Indigenous with studio space in what used to be Hogan’s Alley, how do you participate in conversations while being an ally?

M/K: It starts with being mindful about the space you’re taking up. There’s so much of queer culture that borrows or steals from Black culture, and it’s important to acknowledge that. It’s also important to reflect on who you surround yourself with. Recently, when I’ve been contacted for gigs, I’ve been doing more research about how the organization is set up, and whether they have only white people on their boards. It’s mind blowing sometimes, especially when it’s an advocacy group whose mandate is for the uplifting and sharing of stories of people of colour, while they don’t have any people of colour in positions of power in their organization.

S/V: Make sure you’re listening to Black people and doing what they have said they need you to do. Just because you’re doing something with good intention, and just because everyone else is doing it, doesn’t mean it’s helpful. Be aware of our position as allies, but make sure to ask and to listen to the right people.

M/K: It’s also important for people who have the means to redistribute their resources. There are so many organizations and places you can donate your money to.

CT: Are there activities or practices that are helping you with your mental health and working through 2020?

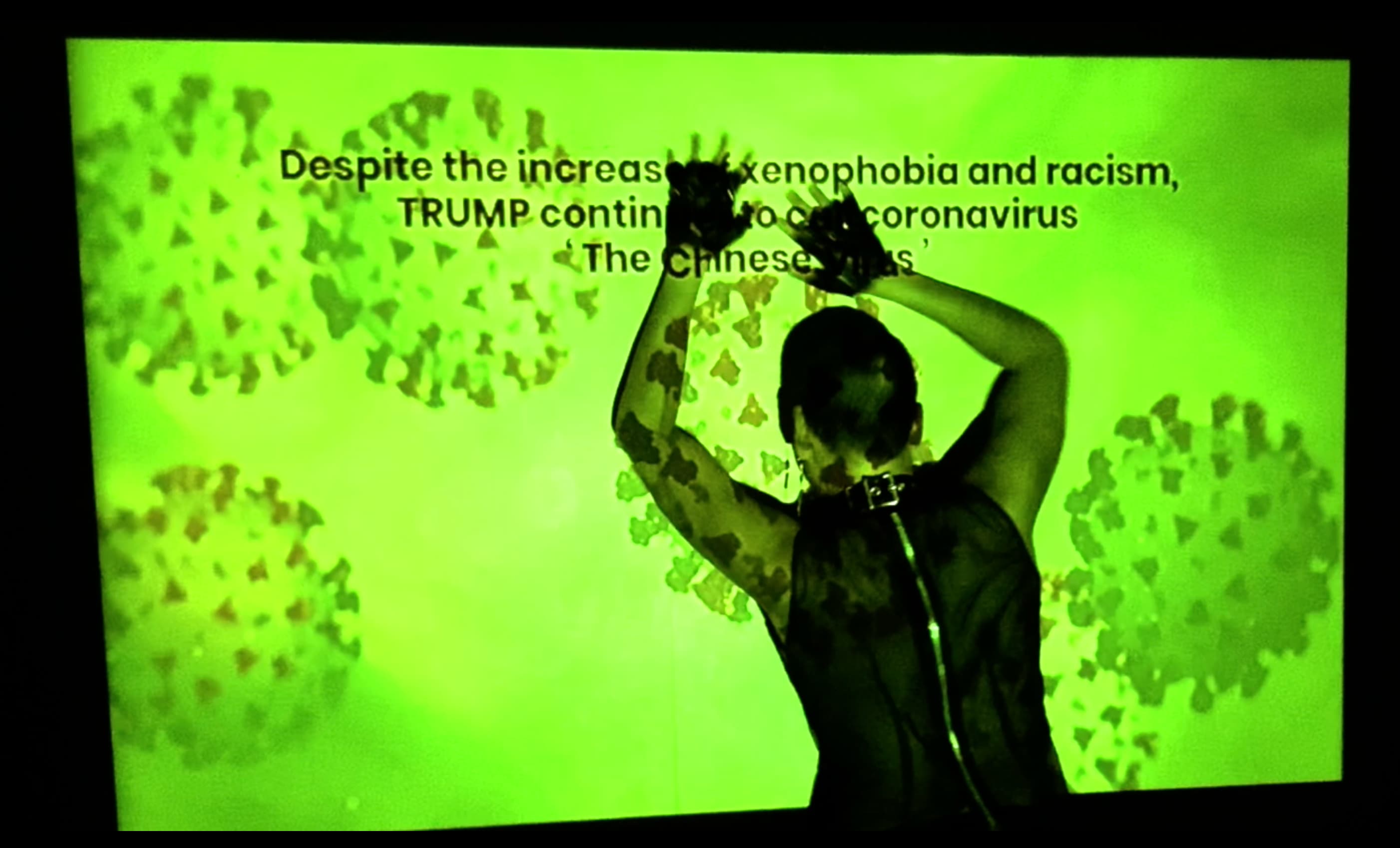

S/V: When drag started moving online, I did a couple of numbers that were addressing racism against Asians because of Coronavirus. Having those big shows that people are viewing from all over the world and hearing comments helped sustain my mental health for a little while. Collaborating with the other members of House of Rice really helps with my mental health because I am able to connect with the family that I created. Keeping those connections, knowing our boundaries, and accepting the fact that should anything happen, none of this is our fault. I’m thankful for being able to connect with friends and family that I trust and love.

CT: What has been your biggest worry during 2020?

M/K: When this all first started happening, I was really worried financially. I had stopped working a few weeks before the mandated shutdown, so I was already sort of broke, and now I’m not working at all. This was before the Canada Emergency Response Benefit. I was doing some online shows, and people were really generous with their donations. Then it became clear just how serious COVID-19 is. It’s funny how my brain was wired to think money is more important than my body. Then, in June, it was seeing the Black Lives Matter protests gain momentum with the murders of George Floyd and Brianna Taylor. The political state of the world feels so much more precarious than it ever has been. In Chinatown, too, we’ve been seeing people close their doors. All urban organizations and fabrics just seem to be so precarious.

S/V: The biggest concern for me is my family in Ontario. I saw my newborn niece for the first time briefly in August. My other sister just gave birth in June. I haven’t been able to see her, and I don’t know if there’s a chance for me to go back. At the beginning of COVID-19 I was taking it very lightly. I thought, “I’m still working, it’s fine, things are going to be fine”. Then I noticed local businesses were closing down. It started to hit me that it might be a long time before I get to see my sisters. If anything were to happen to my sisters, or my parents, would I just be stuck here hearing the news, but not be able to do anything about it? That day on my walk to work, I started crying. Reality just hit me really hard at that point.

CT: What have you learned about yourself during these really difficult times?

M/K: I’ve been doing a lot of internal work and self-reflection. Recently, I was able to vocalize it and come out as trans.

CT: Congratulations!

M/K: I think that’s been a focal point of my literal transformation. Like Van was saying, there are elements of the virus experience that have been a bit of a gift. Before COVID-19, I spent so much time working that I didn’t have time to spend with myself. Now it’s the inverse, and I’m finally able to confront all these things that I’ve been processing since I was a kid but have never actually looked at in the face for what they are. Now I’m able to love that about myself.

CT: What is a message that you want to convey with your art?

S/V: It changes with what’s going on in the world and in our lives. When the Orlando Pulse shooting happened, I did a candlelight performance to honor all the people that had died. When something happens in the world that we feel we need to address, we come up with performance numbers in response to it. Our aesthetics and our drag personas are very political because queer Asians are underrepresented, and we create visibility and increase representation for the people who need to see it by doing what we do.

M/K: Yeah, It’s not so much there’s an obligation to do a drag number that’s political, because queer spaces are so inherently political. I think it’s important not to divorce political or deeply critical thinking from party spaces. I’ve always seen our drag as being a waypoint. Like, hold up. There are terrible things happening.

S/V: Yeah, be aware of it, acknowledge it, think about it, and then keep dancing.

CT: Are there ways that you are continuing to do drag right now?

M/K: I think we’re both on a little bit of a performance break. I’ve done a few fundraisers where the revenue is donated to an organization. I recently did a number reciting Mark Aguahar’s poem “Litanies to My Heavenly Brown Body”, which was very important to me. I think the yellowing of bodies is a further division from brownness in how I conceive those things. I think making art that sparks difficult conversations has been important to me. This virus has brought an upsurge of anti-Asian racism. The model minority myth has real implications in the world especially in North America, but it doesn’t protect you from being perceived as the yellow peril. This yellow peril sentiment can be turned on at any time, and if you are in a certain space, there is so much rhetoric that can be used against you regardless of how much material possessions, land, or success you’ve accumulated, because of the white lens.

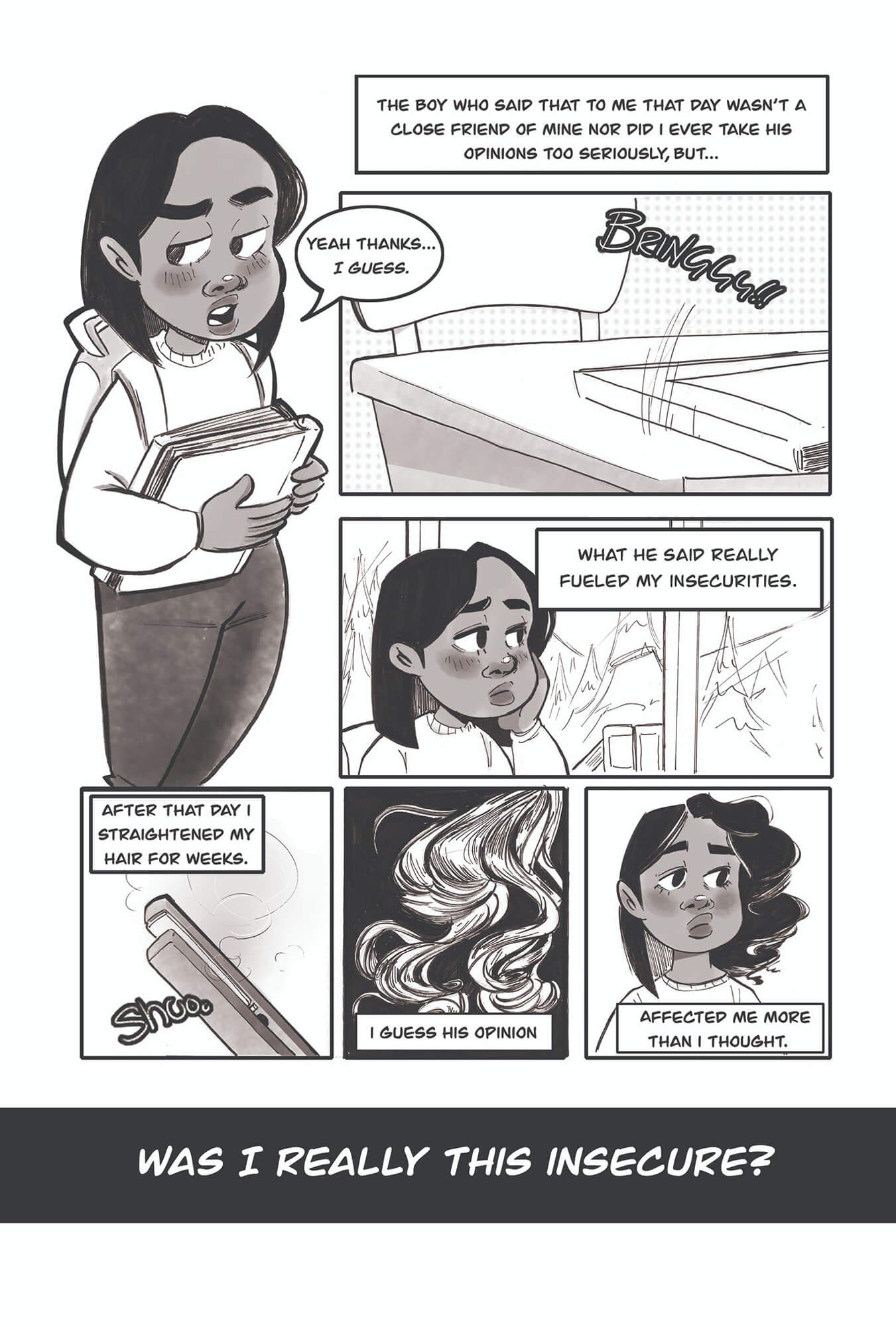

S/V: I’m Vietnamese and South East Asian. I have darker skin. Growing up, I’ve always been under the impression that having darker skin is not as desirable as having lighter skin, because darker skin means you’re poor, and your family is working class or farmers. I really had to learn to deconstruct and unlearn that over the last little while. It’s been impactful, and I think it’s an important conversation that comes from the Aguahar poem.

CT: How does bridging these intersections of queerness and cultural identity manifest as resilience?

M/K: I think it was really exciting that these last few Pride in Chinatown events were in very visible public spaces. The queering of Chinatown in a formalized event is quite new. Resilience in this context is being mindful of the fact that queer people have existed in Chinatown forever, and that queer people have existed forever. There’s so much to think about with regards to queer ancestors and queer people who exist in these spaces. It’s important that there are people like Paul Wong who fight for that queer existence by bringing young artists like ourselves into the space to show other people that we exist.

S/V: It’s also important to realize that even though there is so much racism right now, it isn’t the worst that’s happened. Queer and Asian communities have both persevered and survived for long enough that we’ve been able to be ourselves and make space for ourselves. As a demographic, we’ve gone through racism, we’ve gone through the hate, we’ve gone through the struggles. It’s not the end of the world, as much as it might seem like it.

CT: Was it important to you to have these events at the Sun YatSen Garden in Chinatown?

M/K: It’s important to me. I think Sun Yat-Sen Garden is a beautiful space that has very scholarly connotations. Having this queer opera and queer immersive drag experience in this space goes back to our earlier conversation about not divorcing queer political experiences from academia or a party sphere. It’s really about blending those things together.

S/V: We don’t live one-note lives.

M/K: We have to adapt in different spaces, but a person who works at the Sun Yat-Sen Garden isn’t only defined by their work there. They have other aspects to their identity, too. A person has so many various capacities, and I think it’s important to have a space where you can be all of yourself at the same time.

S/V: It’s about being able to be all our identities in one space, rather than feeling like we have to reserve parts of our identities for certain spaces and certain times. Obviously timing and space are important, but it’s important to be able to explore everyone’s identities in a safe way. Just knowing that we could bring our queer selves to the Sun Yat-Sen Garden and to Chinatown was an important experience.

CT: What does that mean to you to have your studio in Chinatown?

M/K: Having a studio here and living here has been really meaningful to me on a psychological and emotional level, because I get to practice what I do in this neighborhood. In a lot of ways I’m really grateful that I ended up here. It’s part of my history.

CT: What does it mean to recontextualize an art form from your own culture?

M/K: It’s something I’ve been processing throughout my whole drag career. On one hand, I hesitate to claim Cantonese opera because I haven’t studied it. But on the other hand, there is so much of it that is part of my story, and part of who I am. I think it’s important to introduce those things to a wider audience and to contextualize them because I think the queerness of it has always existed. I don’t think I’m doing anything revolutionary.

S/V: It’s about reframing it. It’s taking what we know as our culture, and putting it in a different form that’s exciting to audiences now. If the traditions stay the same, and we’re not interpreting them in our own way, it’s never going to reach who we want it to reach. I think of it as trying to bring awareness to our cultures so that people are more interested in learning about them.

M/K: While it’s important to think about your intentions behind making art, the effect of your intention is out of your control once you put it out into the world. I’ve had to get used to the idea of relinquishing the control over how people will perceive what I do. I’ve had people criticize what I do as being disrespectful because I don’t practice opera or lion dancing. Cultural practices are sacred to people, and that is so valid. Criticism might upset me when my intentions are misunderstood, but it really informs my future decisions. The commodification of culture is a huge topic to unpack. It’s become a part of every conversation I have with myself when I’m doing something new.

S/V: Checking these boxes is a fine balance, because if we were trying to follow a more traditional route, we would never have queer lion dancing and trying to bring women and femmes into the practice, which is traditionally not allowed. We need to balance respect for tradition while at the same time break barriers so we can include everyone.

CT: Speaking of intent and audience, who is your audience?

M/K: I’m creating my art for gender variant people. I think that’s at the heartof who I want to create work for because that’s how I see myself, and stuff like this was missing in a lot of art that I was consuming as a kid and throughout university. There’s such an under-representation of queer Asians from all cultures. When I do what I do, especially when it’s culturally informed, I’m thinking of those people who have never seen work like this on a stage, especially in a white space, or people who think they could never do something like this because of the way their families talk about queerness.

S/V: I’m trying to create to show people that drag is not so scary. There’s space for authenticity in it for you to be yourself and explore all parts of yourself, and you don’t have to follow these social norms of your parents or traditions. That’s the audience that I tend to target.